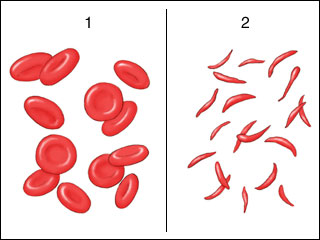

Sickle Cell Anemia

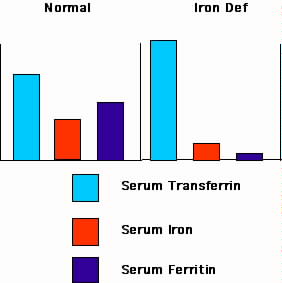

Iron Deficiency Anemia

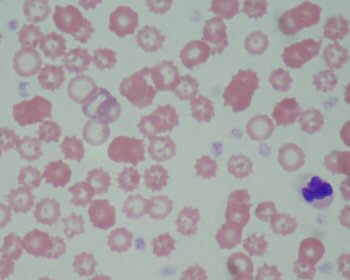

Anemia

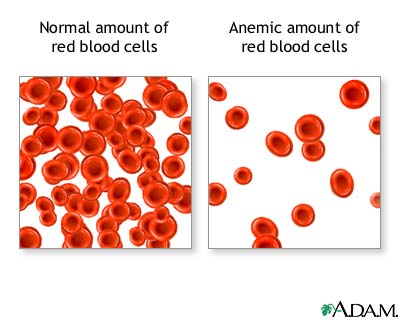

ANEMIA

Sickle Cell Anemia |

|

Iron Deficiency Anemia |

|

Anemia |

Introduction

Maybe your day's so packed with things to do that you hardly have time to grab breakfast, let alone make sure you're eating right the rest of the day. Perhaps you're staying up late to get your homework finished and missing out on the sleep you need. The fact is, lots of teens are tired. And with all the demands of school and other activities, it's easy to understand why.

For some people, though, there may be another explanation for why they feel so exhausted: anemia.

What Is Anemia?

To understand anemia, it helps to start with breathing. The oxygen we inhale doesn't just stop in our lungs. It's needed throughout our bodies to nourish the brain and all the other organs and tissues that allow us to function. Oxygen travels to these organs through the bloodstream - specifically in the red blood cells.

Red blood cells, which are manufactured in the body's bone marrow, act like boats, ferrying oxygen throughout the rivers of the bloodstream. Red blood cells contain hemoglobin, a protein that holds onto oxygen. To make enough hemoglobin, the body needs to have plenty of iron. We get this iron, along with the other nutrients necessary to make red blood cells, from food.

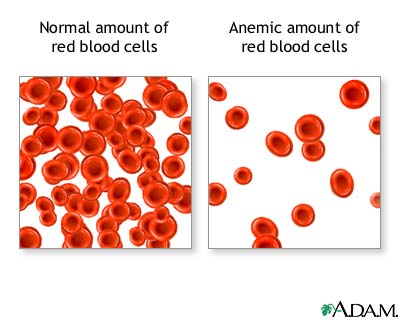

Anemia occurs when a person has fewer red blood cells than normal. This can happen for three main reasons: Red blood cells are being lost, the body is producing them at a decreased rate, or they are being destroyed in the body. Each of these causes is linked to a different type of anemia:

Blood Loss

When a small amount of blood is lost, the bone marrow is able to replace it without a person becoming anemic. But if a large amount of blood is lost over a short period of time, which can happen if someone is in a serious accident, for example, the bone marrow may not be able to replace the red blood cells quickly enough.

If someone loses a little blood over a long period of time, it can also lead to anemia. This can happen in girls who have heavy menstrual periods, especially if they don't get enough iron in their diets.

Iron Deficiency Anemia

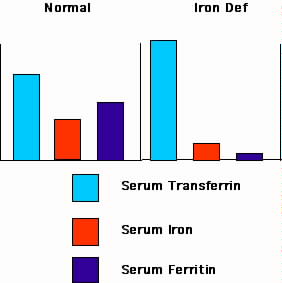

Iron deficiency anemia is the most common type of anemia in U.S. teens. It occurs when a person's diet is lacking in iron. Iron deficiency - when the body's stores of iron are reduced - is the first step towards anemia. If the body's iron stores aren't replenished at this point, continuing iron deficiency can cause the body's normal hemoglobin production to slow down. When hemoglobin levels and red blood cell production drop below normal, a person is said to have anemia.

There are other nutritional reasons why a person may not be making enough red blood cells. Vitamin B12 and folic acid are needed to make red blood cells, so it's important to get enough of these nutrients in your diet. If the bone marrow is not working properly because of an infection, chronic illness, or treatment like chemotherapy, anemia may also develop.

Hemolytic Anemia

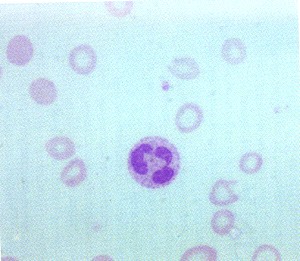

In a person with hemolytic anemia, the lifespan of the red blood cells is shorter than normal. When blood cells die off early, the bone marrow is unable to keep up with production. This can happen for a variety of reasons. A person may have a disorder like sickle cell anemia. In other cases, the body's own immune system can cause destruction of red blood cells. Antibodies can be formed as a reaction to certain infections or drugs that attack the red blood cells by mistake.

Why Do Teens Get Anemia?

Because teens go through rapid growth spurts, they can be at risk for iron deficiency anemia. During a growth spurt, the body has a greater need for all types of nutrients, including iron.

After puberty, girls are at more risk of iron deficiency anemia than guys are. That's because a girl needs more iron to compensate for the blood lost during her menstrual periods. Pregnancy can also cause a girl to develop anemia. And, if a girl is on a diet to lose weight, she may be getting even less iron.

Vegetarians are more at risk of iron deficiency anemia than people who eat meat are. Red meat is the richest and best-absorbed source of iron. Although there is iron in grains, vegetables, and some fruits and beans, there's less of it. And the iron in these food sources is not absorbed by the body as readily as the iron in meat.

Anemia is not contagious, so you cannot catch it from someone who has it.

What Are the Symptoms?

It's easy for people to overlook the symptoms of anemia because it often happens gradually over time. Looking pale can be a sign of anemia because fewer red blood cells are flowing through the blood vessels. The heart will beat faster in an effort to pump the same amount of blood and oxygen to the body, so the pulse may be faster than normal.

As anemia progresses, a person may feel tired and short of breath, especially when climbing stairs or working out. Iron deficiency, which occurs before iron deficiency anemia develops, may affect a person's ability to concentrate, learn, and remember.

How Is Anemia Diagnosed?

If you visit a doctor for suspected anemia, he or she will probably give you a physical examination. The doctor will also ask questions about any concerns and symptoms you have, your past health, your family's health (such as whether anyone in your family has anemia), any medications you're taking, any allergies you may have, and other issues. This is called the medical history.

As part of this medical history, your doctor may ask specific questions about the foods you eat. If you're a girl, the doctor may ask questions about your periods, such as how heavy the flow is, when you got your first period, how often you menstruate, and for how many days.

If your doctor suspects you are anemic, he or she will probably take a blood sample and send it to a lab for analysis. This will determine, among other things, the number, size, and shape of your red blood cells, the percentage of your blood that is made up of red blood cells, and the amount of hemoglobin present in the blood. With this information, a doctor can determine if a person is anemic. A doctor may order additional tests, depending on what he or she suspects is the cause.

How Is Anemia Treated?

The treatment of anemia depends on what's causing it. If the anemia is caused by iron deficiency, your doctor will probably prescribe an iron supplement to be taken several times a day. Your doctor may do a blood test after you have been on the iron supplement. Even if the tests show that the anemia has improved, you may have to continue taking iron for several months to replenish your iron stores.

Because some people become nauseated if they take an iron supplement on an empty stomach, it can help to take it with food. Vitamin C boosts iron absorption, so drink a glass of orange or grapefruit juice when you take your iron. There are other steps you can take to increase the chances that the iron you get from your food will be absorbed by your body. For example, avoid drinking tea with food because a substance in tea called tannin reduces the body's ability to absorb iron found in the food or supplement. Milk can also interfere with iron absorption, so don't pair milk with iron-rich foods if you are concerned about getting enough iron.

Some people need more iron than others: Girls need more than guys, for example. And a girl who has heavy periods has a greater need for iron than a girl who has a light flow.

To make sure you get enough iron, eat a balanced diet every day, starting with a breakfast that includes an iron source, such as an iron-fortified cereal or bread. Lean meat, raisins, spinach, eggs, dried beans, and molasses are also good sources of iron.

If a person's anemia is caused by a medical condition, doctors will work to treat the cause. People with some types of anemia will need to see a specialist who can provide the right medical care for their needs.

The good news is that for most people anemia is easily treated. And in a few weeks you'll have your energy back!

Disclaimer: This information is not intended be a substitute for professional medical advice. It is provided for educational purposes only. You assume full responsibility for how you choose to use this information.

Updated and reviewed by: James Fahner, MD

Date reviewed: September 2004

Originally reviewed by: Maureen F. Edelson, MD, and Rita S. Meek, MD